Really. “Form follows function” and “less is more” are phrases commonly associated with the modernist movement of the Bauhaus. But did you know where the German Bauhaus of the 1920s got their inspiration? From the eighteenth-century American Shakers and their famous Shaker furniture.

The Shakers and their famous Shaker chairs and Shaker chests also directly inspired the Danish Modern movement known for its simplicity, purity of form, and grace.

Who are the Shakers? Of the hundreds of early experiments in communal living in colonial America, the Shakers were the most successful and enduring. The Shakers started in England as a dissident Protestant sect known as “Shaking Quakers” for the wild form of dancing they practiced during intense prayer sessions. Under persecution from the English, eight of the faithful fled to America in 1774 led by Mother Ann Lee.

Who are the Shakers? Of the hundreds of early experiments in communal living in colonial America, the Shakers were the most successful and enduring. The Shakers started in England as a dissident Protestant sect known as “Shaking Quakers” for the wild form of dancing they practiced during intense prayer sessions. Under persecution from the English, eight of the faithful fled to America in 1774 led by Mother Ann Lee.

Lee and her band of merry followers settled in New England but quickly spread, establishing Shaker communities from Maine to Florida and as far west as Ohio and Indiana. Surprisingly, Shakers are celibate, so they can only perpetuate and thrive by recruiting new adult members and by taking in orphans, a practice that was eventually made illegal in the 1960s. Children were not raised as Quakers but were allowed to choose when they turned 21. Those who chose to leave were first given money, tools, and a trade. That trade was usually furniture making.

“Hands to work, hearts to God” was Ann Lee’s motto. And when those hands weren’t working the fields, they were busy building houses and the furniture with which to furnish them. Mother Lee established a strict set of maxims including “simplicity is the embodiment of purity and unity”, “beauty rests in utility”, “that is best which works best” and, most famously, “God is in the details.” (150 years later, Mies van der Rohe paid homage to Lee, with a wry spin, when he coined the phrase “The Devil is in the details.”)

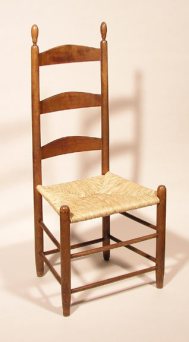

The Shakers strove to create an environment that was clean, orderly and free of distraction so they could worship with pure hearts and minds. This meant a blanket rejection of materialism, vanity, and decoration for decoration’s sake. This is reflected in their furniture, notable for its lack of adornment.

Shaker style furniture was also seen as innately American in its rejection of anything European or British, and demand among non-Shaker colonists was strong in the aftermath of the Revolutionary War. The Shakers began selling their furniture to the public in 1789 and continued to do so until 1947. Most Shaker style furniture made today is mass produced by mainstream furniture makers. New pieces by the rare remaining Shaker artisan sell for many thousands of dollars.

Popularity of Shaker style furniture surged again after the Civil War as a rebuke to the over-adornment of the Victorian age with its excessive ornamentation and gingerbread. The Shakers introduced a catalogue in 1870, which they distributed nationally, that offered chairs, tables and other pieces in a variety of sizes.

Shakers are often mistakenly thought to be luddites, like the Amish, but nothing could be further from the truth. The Shakers have always embraced technology and welcomed any innovation that saved time, which they believed belongs to God. Their inventions numbered in the hundreds, many of which we still take for granted today including the flat broom (replacing bundled sticks), the circular saw, the common clothes pin and the rotary oven. They were the first to sell packaged seeds, the first to popularize photography, the first adopters of electricity and automobiles. They even invented the automatic washing machine with powered agitators which they exhibited at the 1876 World Exhibition in Philadelphia. They became wealthy selling their washing machines to hotels all over the world.

It was at that World Exhibition that the Shakers saw Thonet’s remarkable bentwood furniture from Vienna and quickly adopted the technique, integrating it into their furniture designs and famous Shaker boxes.

So the next time you see a Shaker chair, think of Thomas Merton, the Trappist monk and scholor who said “The peculiar grace of a Shaker chair is due to the fact that it was built by someone capable of believing that an angel might come down and sit on it.”